When a Single Electric Shock Reshapes a Nation’s Safety Landscape: Lessons from the Multi-Employer Worksite Crisis

When a Single Electric Shock Reshapes a Nation’s Safety Landscape: Lessons from the Multi-Employer Worksite Crisis

When a Single Electric Shock Reshapes a Nation’s Safety Landscape: Lessons from the Multi-Employer Worksite Crisis

The Incident That Changed Everything

After analyzing thousands of critical incidents, I’ve observed that fatalities, while tragically common, rarely catalyze systemic change. Yet sometimes a single non-fatal incident exposes such profound failures that entire industries must reckon with their practices.

The August 4, 2025 incident at a POSCO E&C expressway project in Gwangmyeong, South Korea represents such a watershed moment. When a Myanmar subcontractor suffered an apparent electric shock inspecting a flooded underground pump, the worker survived but was critically injured. Yet this incident triggered immediate shutdowns across multiple worksites, raids by authorities, the CEO’s resignation, and implementation of tougher national penalties for repeat fatal accidents.

What made this incident so catalytic? Not its singular severity, but how it crystallized years of accumulated safety failures and exposed fatal flaws in how modern industry manages complex, multi-employer worksites.

Anatomy of a Preventable Tragedy: The Swiss Cheese Alignment

Viewing this through James Reason’s “Swiss cheese” model reveals a disturbing “trajectory of accident opportunity”—multiple defensive layers failing simultaneously to create a clear path to disaster.

Organizational Conditions: The multi-employer interface created ambiguous accountability structures. When workers from different companies, with varying safety standards and reporting structures, converge on a single worksite, the question “who is responsible for this worker’s safety?” becomes dangerously unclear. Add resumption pressure—the urgent need to restart work after weather delays—and you have rushed decision-making and bypassed safety protocols.

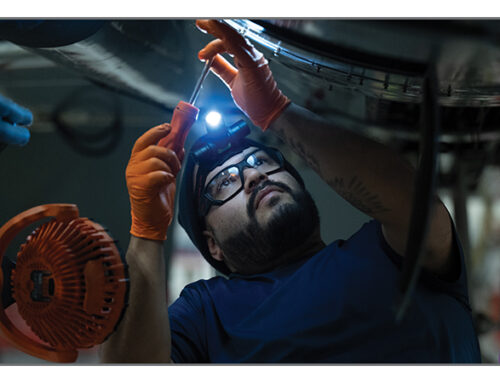

Unsafe Supervision: The incident exposed critical gaps in supervisory oversight, particularly regarding authority to implement energy isolation procedures. Who had authority to lock out the pump? When authority is unclear, critical safety steps fall through cracks. This pattern emerges repeatedly in OSHA’s database: unclear chains of command in multi-employer settings create deadly ambiguities.

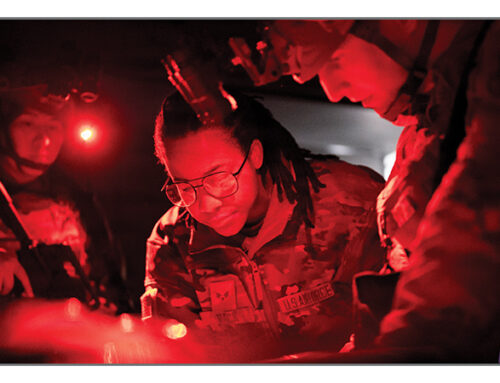

Preconditions: The flooded underground environment created multiple compounding risks. Water and electricity form a lethal combination, yet the worker apparently lacked appropriate PPE. Potential language barriers may have prevented critical safety communication. These aren’t unfortunate circumstances—they’re predictable hazards that proper safety management should anticipate and mitigate.

Unsafe Acts: Someone decided to work near an energized pump in hazardous conditions. But was this individual failure, or the inevitable result of systemic pressures and communication breakdowns? When workers lack clear guidance, face production pressure, and cannot effectively communicate concerns due to language barriers, unsafe acts become almost inevitable.

The Hidden Crisis: Ad Hoc Teams in High-Risk Environments

This incident illuminates what I believe is the single most important yet least discussed threat to industrial worker safety: the challenge of ad hoc team coordination in multi-employer environments.

Modern construction, manufacturing, and energy projects increasingly rely on complex networks of contractors, subcontractors, and contingent workers. These workers must form instant teams—what organizational psychologists call “ad hoc teams”—often with people they’ve never worked with, who report to different supervisors, follow different procedures, and may not speak the same language.

The U.S. Navy recognized this challenge decades ago. Following tragic incidents in the 1980s, they launched the Tactical Decision Making Under Stress (TADMUS) project. This research identified how ad hoc teams struggle with “implicit coordination”—the ability to anticipate teammates’ actions without explicit communication. When team members don’t share mental models, training backgrounds, or communication protocols, performance degrades rapidly under stress.

Yet more than thirty years after TADMUS, industrial safety still hasn’t fully absorbed these lessons. Economic pressures driving contractor networks remain powerful, while safety implications stay hidden until tragedy strikes.

The Language Barrier Multiplier Effect

The involvement of a Myanmar worker in a Korean worksite adds another critical dimension. Language barriers don’t just impede communication—they fundamentally alter power dynamics and safety culture. When workers cannot effectively communicate hazards, ask questions, or refuse unsafe work, they become uniquely vulnerable.

Research from international construction projects shows that foreign workers, particularly those from developing nations working in industrialized countries, face significantly elevated injury rates. Language barriers contributed to approximately 25% of incidents involving foreign workers.

Moreover, limited authority over a contractor co-worker restricts influence on their safety behavior. When you add language barriers, the ability to intervene when observing unsafe conditions virtually disappears. A Korean worker seeing a Myanmar colleague about to make a dangerous decision may lack both the authority and linguistic tools to intervene effectively.

The Systemic Response: Beyond Individual Blame

What makes the POSCO E&C incident significant is not just what happened, but what happened next. The immediate shutdown of multiple worksites, regulatory raids, and CEO’s resignation signal recognition that this was not merely individual failure but systemic breakdown requiring systemic solutions.

The implementation of tougher national penalties for repeat fatal accidents suggests South Korean authorities recognized a pattern safety professionals have long understood: companies experiencing multiple serious incidents aren’t just unlucky—they have fundamental safety management deficiencies. That a non-fatal incident triggered such dramatic action indicates regulators saw this as symptomatic of deeper, potentially catastrophic risks.

The Path Forward: Reimagining Safety Training

This incident inspires immediate upgrades to safety training, particularly in Extended Reality (XR) applications. While many XR practitioners focus on “better fidelity”—making virtual environments look more realistic—we’re missing the deeper challenge. We need to capture the intricate team dynamics formed by ad hoc teams.

Effective safety training for modern industrial environments must simulate not just physical hazards but the social and organizational complexity of multi-employer worksites:

• Communication challenges: Simulating language barriers and teaching universal safety signals

• Authority ambiguities: Training workers to navigate unclear command structures while maintaining safety standards

• Cultural differences: Helping workers understand how different cultural backgrounds affect safety behavior

• Team formation skills: Teaching rapid team integration techniques adapted from military and emergency response

The Navy’s TADMUS research showed teams could develop “shared mental models” even when members had never worked together. By establishing common frameworks and standardized communication protocols, ad hoc teams could perform nearly as well as established teams. Industrial safety training must adapt these insights.

A Call to Action

At the recent Augmented Enterprise Summit, this issue—the safety challenges of multi-employer, multi-cultural work environments—was mentioned only briefly. Yet it sits at the top of my personal list of threats to industrial worker safety. As global supply chains become more complex and specialized contractors proliferate, this trend will only grow more dominant.

We cannot wait for another tragedy to force change. Every organization operating multi-employer worksites must ask:

• Do we have clear, unambiguous safety authority structures that transcend corporate boundaries?

• Are we providing adequate language support and cultural integration for all workers?

• Have we adapted our training to address the unique challenges of ad hoc team formation?

• Are we learning from military and emergency response research on high-stakes team coordination?

The True Cost of Complexity

The incident in Gwangmyeong reminds us that 21st-century workplace safety isn’t just about hazard recognition and personal protective equipment. It’s about managing the complex human systems that emerge when diverse groups of workers, each answering to different authorities, standards, and rules, come together to perform dangerous work.

As we await official first-hand information from the investigation, one thing is clear: traditional approaches to industrial safety, developed for stable workforces in single-employer environments, are inadequate for today’s complex industrial reality. The Swiss cheese model shows us how accidents happen, but preventing them requires reimagining our entire approach to safety in multi-employer environments.

Every day that passes without addressing these systemic issues is another day when workers like the Myanmar subcontractor in Gwangmyeong face preventable risks. Their safety depends not on their individual vigilance alone, but on our collective willingness to confront and solve the complex challenges of modern industrial work.

The CEO of POSCO E&C has stepped down. Worksites have been shuttered. Regulations have been tightened. The question now is whether the rest of the industrial world will learn from this incident, or whether we’ll wait for our own crisis. Given what’s at stake—human lives, corporate reputations, and social license to operate—the choice should be clear.